By C1905618

The glitz and glamour surrounding the West End and Broadway are the hottest places to see our names up in lights. The LGBTQ+ community have become synonymous with all things theatre, especially in the UK. Anyone and everyone are welcome on the stage. Theatres and the UK government have even developed policies around inclusivity to create space for this. But is LGBTQ+ presence on stage any more visible than in previous years?

Notable cultural quarters like Cardiff and London overflow with spaces for LGBTQ+ people to thrive. Theatre companies and groups receive substantial funding and appointed policies ensuring equal opportunities for all and saying a big no-no to the discrimination of creative practitioners. Thanks to the Equality Act of 2010 and theatre policies improving equality in the creative sectors, the theatre has become a place where LGBTQ+ presence thrives with career opportunities and reoccurring LGBTQ+ storylines… Right?….

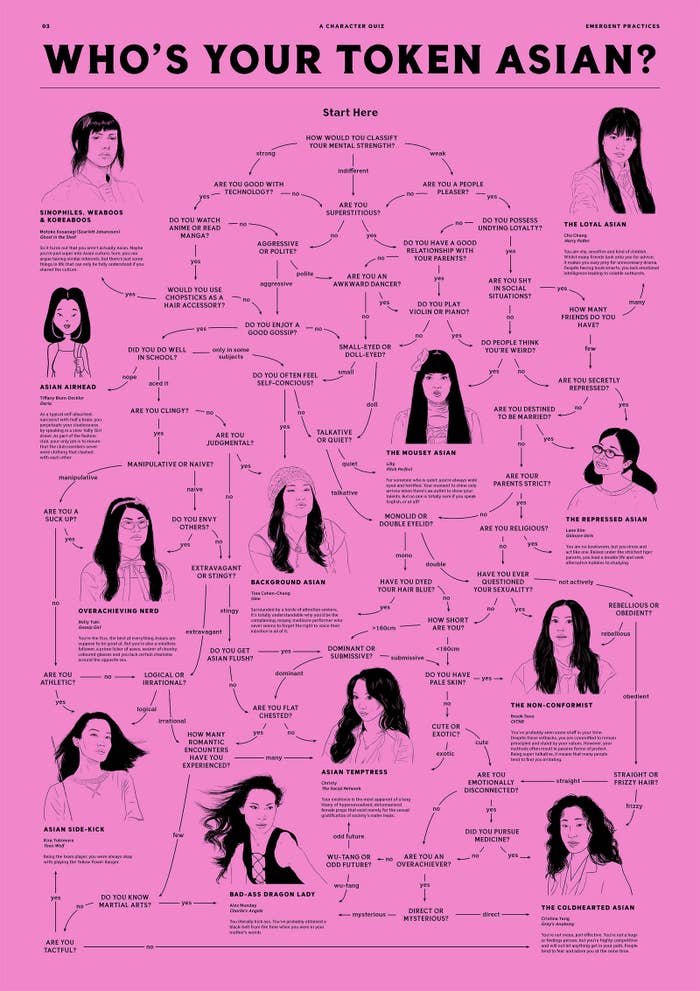

Letters Waiting in the Wings

Source: Broadway Box Photo Gallery via Google Images

A colourful portfolio of LGBTQ+ storylines reoccurs annually on British stages and is touring globally. Popular shows from Kinky Boots – a musical based on the British film surrounding a shoe factory and drag culture – to smaller musicals such as Hedwig and the Angry Inch – a musical covering a botched sex-change operation and exclusion of a German emigrant rock singer. Furthermore, Drag performances and storylines are entering local theatres and the Westend through arrangements such as Everyone’s Talking About Jamie. But do theatres’ associations with queerness translate equality on and off-stage presence?

Source: MsMojo via YouTube

Notably, the Sherman Theatre’s 2022 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream reimagined Shakespeare’s classic theatre production. The play, originally written in a heterosexual context, was adapted to portray the lovers as a lesbian couple. The Sherman Theatre’s policies surround ‘tell[ing] local stories with global resonance’ and a place for everyone. Their contribution to LGBTQ+ visibility through their productions demonstrates these policies. Yet, with this fruitful collection of theatre performances, acronyms in the LGBTQ+ continue to be invisible on the stage. The Gs and Ls are growing in visibility across theatre, but what about the others? What about the community’s Bs, Ts, As, and Ps who wish to see themselves through characters onstage?

Statistically, the UK is not lacking in LGBTQ+ citizens. The Gender identity, England and Wales: Census 2021 received 45.7 million respondents aged 16 and over on their gender identity. Cardiff notably had the highest percentage of respondents who identified as trans men (0.12%) and those who identified as trans women (0.13%).

A similar census conducted on sexual orientation received 45.7 million respondents 16 and over. 1.5 million respondents identified with LGBTQ+ sexual orientations. London holds the highest number of LGBTQ+ respondents (4.3%) in the English region, while Cardiff holds the highest (5.3%) in the Welsh region. LGBTQ+ individuals are creating a large community in these spaces, but why is it so hard to find theatres and productions dedicated to their presence?

Is eradication of the past as problematic as previous discourses?

Younger generations, in particular, have identified the outdatedness of queer representation through previous theatre performances. How younger generations feel about policies implemented to discontinue theatre performances that cause discomfort or offence is understandable. They surface the question: should theatre abolish the continuation of problematic discourses to prevent this?

Notably, the presence of outdated LGBTQ+ storylines and characters on the stage can be an excellent opportunity to learn from previous mistakes. It may sometimes feel uncomfortable, but spaces must be left for queer historical theatre, even if they do not align with updated ideas. These spaces will allow for recognition of theatre’s contribution to the LGBTQ+ community and demonstrate how far they have come. Their existence does not excuse new productions using past problematic discourses, however. Policies should protect their significance in developing more updated understandings of LGBTQ+ representation that will contribute to equality on stage.

All this queerness, nowhere to go.

Source: BGD Interview with Panmai via Google Images

Theatre policies ensuring the safety and inclusion of minority groups are ubiquitous in the UK. Unfortunately, including LGBTQ+ members are still deemed a political statement in the UK and elsewhere. Policies and even laws aren’t always contributing to equality for creative sectors.

Exemplary, 2014 saw the formation of India’s first transgender theatre group, Panmai. The theatre group created and conducted by trans activists – Living Smile Vidya, Angel Glady and Gee Imaan Semmalar – aims to provide opportunities to transgender citizens in India. Vidya mentions the transgender struggles of being subjected and restricted to beggary and sex work propelled by anti-LGBTQ+ communities in India. The group’s policy is to create creative careers for transgender individuals, reducing the social exclusion they often experience.

Although the Supreme Court of India’s 2014 verdict recognises transgender individuals as a ‘third gender’ by law, this has not equated to cultural or social acceptance of LGBTQ+ citizens in India. Similar to many theatres across the globe, Panmai’s policy can create a temporary space for LGBTQ+ members but does not necessarily extend outside the group.

Policies of inclusion and equality do contribute to the visibility of some LGBTQ+ members, but others remain absent from the stage. The presence of bisexuals, asexuals, pansexuals, and gender-fluid individuals on the stage is necessary to consider theatre LGBTQ+ fully inclusive. Theatres can create spaces for LGBTQ+ members to experience inclusion, even if they do not receive it off the stage.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/56148691/Screen_Shot_2017_08_11_at_09.58.34.0.png?resize=1200%2C800&ssl=1&crop=1)

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/56148691/Screen_Shot_2017_08_11_at_09.58.34.0.png)